Henslowe's Diary ... as a Blog! is now on hiatus and will be back on 27th December.

This blog attempts to capture the day-by-day life of an Elizabethan theatre by recounting the daily performances at the Rose playhouse by Lord Strange's Men, as recorded in Philip Henslowe's diary. The London theatres were closed on 23 June, 1592 to prevent the spread of plague, and they did not re-open until December of that year. While the Rose was shut, Strange's Men toured their plays around the towns of England.

When we return in December, the daily posts will be back and there will be new plays to discover alongside the old stalwarts. Thank you for reading, and see you then!

Monday, 27 June 2016

Sunday, 26 June 2016

Lord Strange's Men on tour, 1592

When the London theatres closed on 23rd June for the rest of the year, Lord Strange's Men were forced to abandon London and take their plays on tour.

'Touring' was the normal response of Elizabethan playing companies whenever London's theatres were closed. It involved travelling the country from town to town, performing in town halls, large private homes, inns and other venues. Lord Strange's Men would have been familiar with touring, even if they may have undertaken it under duress, preferring the comfort and reliability of their permanent base in the city.

Tracing the 1592 tour of Lord Strange's Men is difficult, because the records are sparse and vague. We know a few of the towns they visited, but the exact dates of the visits are hard to pin down. Nonetheless, thanks to the archival research of the the Records of Early English Drama project, we can reconstruct the approximate journey they took. The following description is indebted to that of Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawrence Manley in their book Lord Strange's Men and their Plays, and to the very useful Patrons and Patronage website.

We don't know which plays the company would have performed, but MacLean and Manley note that the surviving texts of Orlando Furioso and A Knack to Know a Knave require smaller casts than the others and appear to have been shortened, as if they have been adapted to the leaner resources of a tour.

Throughout June and and July the company seems to have toured Kent. They began in Rye on the 24th June, and records survive of their visits to Canterbury, Faversham, Maidstone and Folkestone.

These performances were usually staged at the local town hall or guildhall. Sadly, none of the Kentish halls that Lord Strange's Men visited have survived the passage of time, but we do at least have photographs of Canterbury Court Hall before it was demolished; it's just about possible to imagine performing a play there. The halls were very different in size, shape and structure, so the actors may have had to rapidly improvise when choosing plays and adapting them to the venue.

In August, the company seems to have headed south-west, leaving no traces in the records until they arrived at Bristol in early August, perhaps to catch the end of the St. James Day Fair. They may have performed at a number of venues in this large port city.

Finally, the company headed north, through the Midlands. They were at Gloucester in late September, Oxford on 6th October, and Coventry after that. They also visited Cambridge at some point in their travels.

In Coventry, you can see the only surviving venue of the 1592 tour. This might come as a surprise, since the historic centre of Coventry was famously destroyed by bombing in the Second World War and replaced with a concrete jungle. However, the beautiful St Mary's Guildhall was miraculously preserved. The area surrounding it evokes the medieval streets rather well, and the interior is spectacular. Interestingly enough, the hall is dominated by a giant stained-glass window with an image of King Henry VI at is centre; it would have been amazing to perform Harry VI beneath it.

There is something romantic about the life of the travelling player - what could be more adventurous than to travel the country with a famous and talented cast, thrilling the locals with the wonderful new plays of Elizabethan London? People outside London had few opportunities to see this kind of theatre, so instead of the jaded audiences of the Rose, rolling their eyes at yet another performance of Muly Molocco, we can imagine the provincial audiences being genuinely excited, appreciative and hospitable.

But still, touring had its drawbacks. Although the money was good, and the players were often provided with comfortable lodgings, we can still imagine that bad weather, muddy roads and annoying colleagues could make for an irksome experience. MacLean and Manley note that the company never strayed further than a few days' ride from London, as if they were always hoping to receive news that they could return, and were perhaps longing for the more predictable world of the permanent London theatres.

But they won't be back in London for a long time, so let's leave them on the road and pick up their story on 27th of December...

'Touring' was the normal response of Elizabethan playing companies whenever London's theatres were closed. It involved travelling the country from town to town, performing in town halls, large private homes, inns and other venues. Lord Strange's Men would have been familiar with touring, even if they may have undertaken it under duress, preferring the comfort and reliability of their permanent base in the city.

Tracing the 1592 tour of Lord Strange's Men is difficult, because the records are sparse and vague. We know a few of the towns they visited, but the exact dates of the visits are hard to pin down. Nonetheless, thanks to the archival research of the the Records of Early English Drama project, we can reconstruct the approximate journey they took. The following description is indebted to that of Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawrence Manley in their book Lord Strange's Men and their Plays, and to the very useful Patrons and Patronage website.

We don't know which plays the company would have performed, but MacLean and Manley note that the surviving texts of Orlando Furioso and A Knack to Know a Knave require smaller casts than the others and appear to have been shortened, as if they have been adapted to the leaner resources of a tour.

Kent (June-July)

Throughout June and and July the company seems to have toured Kent. They began in Rye on the 24th June, and records survive of their visits to Canterbury, Faversham, Maidstone and Folkestone.

|

| Canterbury Court Hall in 1910 |

Bristol (August)

In August, the company seems to have headed south-west, leaving no traces in the records until they arrived at Bristol in early August, perhaps to catch the end of the St. James Day Fair. They may have performed at a number of venues in this large port city.

The Midlands (September to November)

|

| The streets around St Mary's Guildhall in Coventry. |

In Coventry, you can see the only surviving venue of the 1592 tour. This might come as a surprise, since the historic centre of Coventry was famously destroyed by bombing in the Second World War and replaced with a concrete jungle. However, the beautiful St Mary's Guildhall was miraculously preserved. The area surrounding it evokes the medieval streets rather well, and the interior is spectacular. Interestingly enough, the hall is dominated by a giant stained-glass window with an image of King Henry VI at is centre; it would have been amazing to perform Harry VI beneath it.

On the road

There is something romantic about the life of the travelling player - what could be more adventurous than to travel the country with a famous and talented cast, thrilling the locals with the wonderful new plays of Elizabethan London? People outside London had few opportunities to see this kind of theatre, so instead of the jaded audiences of the Rose, rolling their eyes at yet another performance of Muly Molocco, we can imagine the provincial audiences being genuinely excited, appreciative and hospitable.

But still, touring had its drawbacks. Although the money was good, and the players were often provided with comfortable lodgings, we can still imagine that bad weather, muddy roads and annoying colleagues could make for an irksome experience. MacLean and Manley note that the company never strayed further than a few days' ride from London, as if they were always hoping to receive news that they could return, and were perhaps longing for the more predictable world of the permanent London theatres.

But they won't be back in London for a long time, so let's leave them on the road and pick up their story on 27th of December...

FURTHER READING

- Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawrence Manley, Lord Strange's Men and their Plays (Yale University Press, 2014), 248-58, 271-8, 342

Saturday, 25 June 2016

Looking back: war and nation in the Rose plays

Having reached the end of this stage of Henslowe's Diary, I had been planning to conclude with some reflections on the plays - both lost and extant - that we've been looking at over the last few months, I wanted to think about the variety of stories that Lord Strange's Men told, but also about the recurring themes and ideas that made their plays distinctive to them.

Unfortunately, I found this entry rather hard to write. That's because I was trying to compose my thoughts on the very day that the UK voted to exit the European Union. I don't mean that I was distracted by the need to stare in horror at the TV (although I was). Rather, it was the unfortunate parallels between what I wanted to write about and what was in the news. In case you are reading this in the distant future, I should explain that the 'Brexit' vote took place following months of public debate that had rapidly veered away from the complex issues of EU policy and had instead degenerated into clumsy arguments about immigration, British/English identity, tradition, and terrorism, all of which had unleashed a cesspool of nastiness and hatred within our sceptred isle.

This background made it rather depressing for me to write that the most-performed play at the Rose was a work of English triumphalism about bashing the French (Harry VI), and that a remarkable number of the other plays drew on the imagery of the Crusades against Islam in the Middle East. I'm generally reluctant to draw specious connections between Renaissance plays and the modern world, but I couldn't help feeling that I was seeing in the popular culture of 400 years ago the same kind of simplistic nationalism that was unfolding in the vacuous discussions on TV.

However, having thought about it a bit more, I've decided that the popular culture on display in the Rose playhouse was in no way as crass and stupid as the Brexit debates. The plays were certainly violent, and they were definitely written during an era of patriotic triumphalism, but it's surprising how little they invoke mindless flag-waving and encourage more complex responses.

The plays of Lord Strange's Men were varied: the company performed histories, tragedies, comedies, and even a pastoral. Despite this, it's very clear that one of their specialities was stage violence: in particular, the audience of Lord Strange's Men enjoyed watching fight scenes.

Most of the plays are about wars - Harry of Cornwall (English civil wars), Harry VI (England vs. France), Jerusalem (the Crusades), Muly Molocco (Moroccan civil wars), The Spanish Comedy (Spain vs. Portugal), Tamar Cam (Mongols vs. the Middle East), Titus and Vespasian (Romans vs. Jews), and Zenobia (Roman civil wars). War may also have been present in Constantine, Brandimer, Friar Bacon and The Tanner of Denmark.

And what better way to make onstage fighting more thrilling than to mix it with triumphalist patriotism? Such a theme would certainly have been very much in tune with the public mood, as England was still buoyant after its defeat of the invading Spanish Armada in 1588. By 1592, England was engaged in a war in France to support French Protestants,

It's no surprise, then, that the Rose's most frequently-performed play was Harry VI, which packed the theatre with spectators who reportedly wept to see the English hero Lord Talbot fight bravely against the French army, and presumably cheered as the English defeated Joan of Arc (who is portrayed as a devil-summoning witch). Another play in the same mode may have been the popular but mysteriously one-off Tanner of Denmark; if it was indeed the play we know as Edmund Ironside, it has an English hero who defeats the brash Danish invaders.

But this kind of straightforward nationalism is actually surprisingly rare in the Rose repertory. England itself rarely appears in the plays, and when it does it's compromised: A Knack to Know a Knave portrays an England filled with sinners, and Harry of Cornwall is about a civil war, a traitor, and a sacrilegious murder. A Looking-Glass for London lectures the city on its similarity to the sinful Nineveh in the Bible.

Of course, tales set in lands far away could still tap into the national mood. The lost Zenobia may have used its eastern warrior heroine to reenact the victories of Queen Elizabeth. The Spanish Tragedy permits its audience to enjoy seeing vicious Spaniards murder each other. A play like Jerusalem might enable its audience to identify with French warriors as they push the Turks from the Holy City, while Tamar Cam may have done the same as its Christianized Mongol protagonist scourged the Islamic world.

If we read those plays that way, we can also see an 'us vs. them' narrative in the surprising number of plays that use the imagery of the Crusades. One thing I had not expected when beginning this blog is the almost continuous theme of war with Islamic nations. Many of the plays are set in the Middle East, and the Crusades are usually somewhere in the background of others. Wars involving Muslims are very important to The Jew of Malta, Muly Molocco, Tamar Cam, and Jerusalem. The Crusades are in the background, if not enormously significant, of Orlando Furioso. There is a possibility that they were also included in Harry of Cornwall, Brandimer and Sir John Mandeville. And on a vaguer level, the topic of war between east and west is present in Titus and Vespasian and Zenobia. Perhaps, then, the topic of Holy War was another, broader dimension of the belligerent nationalism on display in the Rose plays.

But I actually think not...

It's wrong to say that all of the Rose plays tap into a simplistic 'us vs. them' mentality. The Spanish Tragedy, for example, was not simply an excuse to gloat at dying Spaniards; audiences sympathised with the suffering of the grieving father Hieronimo and his desire for revenge. In Muly Molocco, the audience is encouraged to sympathise with the Muslim Abdelmelec against the cruel Muly Mahamet and his European supporters. The play with the most consistently high box office was The Jew of Malta, a satire on hypocrisy in all religions, and on the human ability to use religion to justify crimes - it doesn't single out any one religion for special hatred. Titus and Vespasian may have used the Jewish Wars to satirize religious extremism in England.

And even Harry VI laments the death of English heroes like Talbot and their replacement by squabbling, self-serving politicians, while Edmund Ironside ends with an English machiavel plotting to undermine the hero's triumph. So perhaps we should not automatically assume any of these plays to have produced merely straightforward responses.

The Rose plays are not always well-written and they certainly place great emphasis on spectacle, special effects and, yes, fighting. But if the authors intended their exciting, epic, and exotic tales to indulge in simplistic xenophobia and nationalism, they were doing it all wrong.

Unfortunately, I found this entry rather hard to write. That's because I was trying to compose my thoughts on the very day that the UK voted to exit the European Union. I don't mean that I was distracted by the need to stare in horror at the TV (although I was). Rather, it was the unfortunate parallels between what I wanted to write about and what was in the news. In case you are reading this in the distant future, I should explain that the 'Brexit' vote took place following months of public debate that had rapidly veered away from the complex issues of EU policy and had instead degenerated into clumsy arguments about immigration, British/English identity, tradition, and terrorism, all of which had unleashed a cesspool of nastiness and hatred within our sceptred isle.

|

| Imaginary portrait of Talbot, "the terror of the French", by Thomas Cecil, c.1626-32 |

However, having thought about it a bit more, I've decided that the popular culture on display in the Rose playhouse was in no way as crass and stupid as the Brexit debates. The plays were certainly violent, and they were definitely written during an era of patriotic triumphalism, but it's surprising how little they invoke mindless flag-waving and encourage more complex responses.

Theatre of violence

|

| From Joachim Meyer's swordfighting manual (1570) |

Other plays are not literally about war, but still contain violent scenes, whether they're revenge tragedies such as The Jew of Malta, The Spanish Tragedy and, probably, Machiavel, or whether they're romances like Sir John Mandeville and Orlando Furioso, or Biblical moralities like A Looking-Glass for London.

Indeed, it's hard to find anything sweet and fluffy in the repertory. Even the Italianate comedy Bindo and Ricciardo probably included a horrid death and the moralistic Knack to Know a Knave describes hideous punishments for the bad guys. The only innocuous-seeming play is the lost pastoral Cloris and Ergasto, but for all we know it may have been about shepherds hitting each other with sticks.

This suggests that onstage fighting was one of the specialities of Lord Strange's Men, and that would have fitted with their star Edward Alleyn's reputation for playing larger-than-life warriors. This emphasis on fighting may have been a characteristic of this particular company rather than of early 1590s theatre as a whole. If you look at what Shakespeare was doing around 1592, you find him writing romantic comedies such as The Comedy of Errors and The Two Gentlemen of Verona alongside the gore and war of Titus Andronicus or the Henry VI plays. But there's almost nothing like those at Henslowe's Rose. The Rose was a theatre of violence.

Theatre of triumph

|

| Queen Elizabeth poses with her hand on the globe in the aftermath of the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) |

It's no surprise, then, that the Rose's most frequently-performed play was Harry VI, which packed the theatre with spectators who reportedly wept to see the English hero Lord Talbot fight bravely against the French army, and presumably cheered as the English defeated Joan of Arc (who is portrayed as a devil-summoning witch). Another play in the same mode may have been the popular but mysteriously one-off Tanner of Denmark; if it was indeed the play we know as Edmund Ironside, it has an English hero who defeats the brash Danish invaders.

But this kind of straightforward nationalism is actually surprisingly rare in the Rose repertory. England itself rarely appears in the plays, and when it does it's compromised: A Knack to Know a Knave portrays an England filled with sinners, and Harry of Cornwall is about a civil war, a traitor, and a sacrilegious murder. A Looking-Glass for London lectures the city on its similarity to the sinful Nineveh in the Bible.

|

| Tiepolo, Queen Zenobia Addressing her Troops (c.1725) |

If we read those plays that way, we can also see an 'us vs. them' narrative in the surprising number of plays that use the imagery of the Crusades. One thing I had not expected when beginning this blog is the almost continuous theme of war with Islamic nations. Many of the plays are set in the Middle East, and the Crusades are usually somewhere in the background of others. Wars involving Muslims are very important to The Jew of Malta, Muly Molocco, Tamar Cam, and Jerusalem. The Crusades are in the background, if not enormously significant, of Orlando Furioso. There is a possibility that they were also included in Harry of Cornwall, Brandimer and Sir John Mandeville. And on a vaguer level, the topic of war between east and west is present in Titus and Vespasian and Zenobia. Perhaps, then, the topic of Holy War was another, broader dimension of the belligerent nationalism on display in the Rose plays.

But I actually think not...

Theatre of doubt

_Cropped.jpg/609px-Siege_and_destruction_of_Jerusalem_(f._155v)_Cropped.jpg) |

| Sixteenth century illustration of the Romans destroying Jerusalem |

And even Harry VI laments the death of English heroes like Talbot and their replacement by squabbling, self-serving politicians, while Edmund Ironside ends with an English machiavel plotting to undermine the hero's triumph. So perhaps we should not automatically assume any of these plays to have produced merely straightforward responses.

The Rose plays are not always well-written and they certainly place great emphasis on spectacle, special effects and, yes, fighting. But if the authors intended their exciting, epic, and exotic tales to indulge in simplistic xenophobia and nationalism, they were doing it all wrong.

Apologia

Well, that's what I think anyway. These are of course vast and complex subjects that have been written about in far more detail elsewhere. Every single sentence that I've written above could be debated, and indeed probably has been, by scholars who know a lot more than I do. All I really wanted to get off my chest is that Elizabethan popular culture, as reflected in the Rose plays, is far more intelligent and sophisticated than a Brexit poster...

Friday, 24 June 2016

Looking back: what was popular?

Since the Rose theatre is now closed until December, let's look back at what we've seen taking place there since 19th February.

I created this blog because I was interested in which plays were popular and which were not, and how their popularity rose and fell over time. Writing it did make me realise, however, that it's hard to define exactly what we mean by 'popular'. And it also made me realise how little we know about why the company staged what they did each day. Allow me to explain...

One way of assessing popularity is to look at which plays were performed most frequently. The most-performed play was Harry VI (which is almost certainly the play we now call Shakespeare's First Part of Henry VI). It was staged 15 times in 4 months, being performed on an almost weekly basis.

Here are the figures for the other three 'big hitters', each of which was in the repertory throughout the entire period that we looked at and was normally staged once every 10 days or every fortnight:

Another way to judge popularity is through box office. The highest box office receipt was Harry VI on 3rd March, with 75 shillings. The lowest was A Looking-Glass for London on 8th March with 7 shillings.

But these outlying results aren't very meaningful when considering what we mean by 'popular'. Harry VI achieved amazing box office for a few weeks after its premiere, but then turned into a very average play for the rest of the season. A Looking-Glass for London was catastrophically unpopular one day, but did perfectly well every other time it was revived; perhaps it was simply hit by bad weather. The vast majority of Rose performances hover around the average for box office, which is about 33 shillings, representing a half-full theatre.

Given the above points, the most impressive box office is actually achieved by Marlowe's Jew of Malta. Although not performed as often as some other plays, and never achieving the enormous heights that some occasionally reached, The Jew of Malta almost always achieved box office well above the average and is thus the most consistently popular play. The actors must have looked forward to performing this play, because they could be certain of walking onstage to face a large, happy audience. With almost all the other plays, they never quite knew what they were going to get.

If you're interested, the award for worst play ever thus goes to the lost Constantine: performed once, received a damning 12 shillings, and never looked at again. We do not know what this enigmatically-titled play was about, but clearly London didn't give a damn either way.

A lot of the time, I found myself scratching my head about the company's choices, and what made the box office go up or down. But I did learn a few 'rules' of Henslowe's Rose.

The most obvious rule is that debut performances of new plays always achieve the highest box office. As I explain in detail here, this is probably because the audiences loved novelty and the chance to see something brand new, although it is also conceivable that the company charged extra for new plays.

Another rule seemed to be that performances of a play needed to be spaced out to avoid overkill - the company hardly ever performed the same play in one week, and when they did it often drew a smaller audience (see this example). Relatedly, it seemed that with the frequently-performed plays, absence may have made the audience's hearts grow fonder - I found several instances (for example this one) in which the company held off on performing a play for a couple of weeks, and achieved a higher box office when they brought it back, as if this caused the audience to become keener to see it.

The most enjoyable rule I found, however, was that holiday periods could cause Londoners to flock to the theatre. It was nice to imagine the excitement of actors and audiences on May Day and the week of Whitsuntide as people spent their days off at the playhouse. And especially fascinating was the dismal box office during Holy Week (when Londoners perhaps felt guilty about going to see plays), following by a boom during Easter Week (when London was in a more celebratory mood).

For some reason, this blog gets a huge spike in readership every time The Jew of Malta is mentioned. Conclusion: Marlowe fans are excitable.

Also, the article on Brandimer was inexplicably popular. Conclusion: giants are awesome.

It was quite interesting to follow the ebb and flow of box office, but money isn't everything, so in the next post I'll look back at the plays themselves and consider what we've learned about what audiences at the Rose liked to see.

I created this blog because I was interested in which plays were popular and which were not, and how their popularity rose and fell over time. Writing it did make me realise, however, that it's hard to define exactly what we mean by 'popular'. And it also made me realise how little we know about why the company staged what they did each day. Allow me to explain...

The most-performed plays

Here are the figures for the other three 'big hitters', each of which was in the repertory throughout the entire period that we looked at and was normally staged once every 10 days or every fortnight:

- 13 performances - The Spanish Tragedy by Thomas Kyd

- 11 performances - Muly Molocco (which may or may not have been The Battle of Alcazar by George Peele)

- 10 performances - The Jew of Malta by Christopher Marlowe

These plays were the bastions of Lord Strange's Men, and although they didn't always do that well at the box office - often hovering around the average for the Rose, sometimes lower than average - they could reliably pull in enough of an audience to fill the theatre approximately half-full, or only a bit less.

There are also a bunch of plays that the company revived only once a month or so during this 4 month period. They include:

- 7 performances - The Spanish Comedy (lost)

- 5 performances - Sir John Mandeville (lost)

- 4 performances - Friar Bacon (which may be Robert Greene's Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay or the anonymous John of Bordeaux); Harry of Cornwall (lost); and A Looking-Glass for London and England by Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge

- 3 performances - Bindo and Ricciardo (lost) and Machiavel (lost)

I find the existence of these monthly performances rather puzzling. The frequent performances of the 'big hitters' must have enabled their lines to stay fresh in the actors' memories. By contrast, it must have been a lot of mental effort for the actors to return to plays that they didn't perform for weeks at a time. And most of these monthly plays didn't receive notably bigger or smaller audiences than the 'big hitters'. I wonder why they were relegated to only occasional performances?

Next, we have some plays that might have had the potential to be stalwarts of the stage, but which were introduced too late for us to know whether they would have done so before the plague rudely interrupted:

- 7 performances in 2½ months - Titus and Vespasian (lost)

- 5 performances in 2 months - Tamar Cam, parts 1 and/or 2 (lost)

- 3 performances in 2 weeks - A Knack to Know a Knave

Finally, we have the plays that the company apparently gave up on: Brandimer and Jersualem were performed only twice and all the rest just once. A lot of these may have been old plays that the company tried out and decided weren't worth reviving again. But there are also stranger examples, such as the enigmatic Tanner of Denmark, which never returned after its stellar premiere. And even some of these one-offs don't do particularly badly at the box office (such as Four Plays in One), so it's hard to understand why the company abandoned them and continued to perform others.

Box office

Another way to judge popularity is through box office. The highest box office receipt was Harry VI on 3rd March, with 75 shillings. The lowest was A Looking-Glass for London on 8th March with 7 shillings.

But these outlying results aren't very meaningful when considering what we mean by 'popular'. Harry VI achieved amazing box office for a few weeks after its premiere, but then turned into a very average play for the rest of the season. A Looking-Glass for London was catastrophically unpopular one day, but did perfectly well every other time it was revived; perhaps it was simply hit by bad weather. The vast majority of Rose performances hover around the average for box office, which is about 33 shillings, representing a half-full theatre.

Given the above points, the most impressive box office is actually achieved by Marlowe's Jew of Malta. Although not performed as often as some other plays, and never achieving the enormous heights that some occasionally reached, The Jew of Malta almost always achieved box office well above the average and is thus the most consistently popular play. The actors must have looked forward to performing this play, because they could be certain of walking onstage to face a large, happy audience. With almost all the other plays, they never quite knew what they were going to get.

If you're interested, the award for worst play ever thus goes to the lost Constantine: performed once, received a damning 12 shillings, and never looked at again. We do not know what this enigmatically-titled play was about, but clearly London didn't give a damn either way.

The rules

A lot of the time, I found myself scratching my head about the company's choices, and what made the box office go up or down. But I did learn a few 'rules' of Henslowe's Rose.

The most obvious rule is that debut performances of new plays always achieve the highest box office. As I explain in detail here, this is probably because the audiences loved novelty and the chance to see something brand new, although it is also conceivable that the company charged extra for new plays.

Another rule seemed to be that performances of a play needed to be spaced out to avoid overkill - the company hardly ever performed the same play in one week, and when they did it often drew a smaller audience (see this example). Relatedly, it seemed that with the frequently-performed plays, absence may have made the audience's hearts grow fonder - I found several instances (for example this one) in which the company held off on performing a play for a couple of weeks, and achieved a higher box office when they brought it back, as if this caused the audience to become keener to see it.

The most enjoyable rule I found, however, was that holiday periods could cause Londoners to flock to the theatre. It was nice to imagine the excitement of actors and audiences on May Day and the week of Whitsuntide as people spent their days off at the playhouse. And especially fascinating was the dismal box office during Holy Week (when Londoners perhaps felt guilty about going to see plays), following by a boom during Easter Week (when London was in a more celebratory mood).

Most popular play among readers of this blog

For some reason, this blog gets a huge spike in readership every time The Jew of Malta is mentioned. Conclusion: Marlowe fans are excitable.

Also, the article on Brandimer was inexplicably popular. Conclusion: giants are awesome.

What's next?

It was quite interesting to follow the ebb and flow of box office, but money isn't everything, so in the next post I'll look back at the plays themselves and consider what we've learned about what audiences at the Rose liked to see.

Labels:

Commentary

Thursday, 23 June 2016

23 June, 1592 - The closing of the theatres

Today, the Rose playhouse was abruptly closed, along with all the other theatres in London. Lord Strange's Men no longer had a place to perform and were forced to leave the city. And this blog must therefore come to a sudden halt.

Why? It was apparently all because of that riot that broke out in Southwark a couple of weeks ago. The Privy Council had been informed about it and had decided to enhance security around the city. They explained that they had learned of "certain apprentices and other idle people" who had caused "the late mutinous and foul disorder in Southwark in most outrageous and tumultuous sort". They had now heard that the same people "have a further purpose and meaning on Midsummer Evening or Midsummer Night or about that time to renew their lewd assemblage".

Concerned about these possible future disturbances, the Privy Council therefore ordered the Mayor of London to "set a strong and substantial watch" about the city. But that was not all. They added that "for avoidance of these unlawful assemblies in these quarters", the Mayor should order

This ban on theatre and other gatherings for popular entertainment was to last until "the Feast of St Michael" - that is, 29th September.

This was a very extreme reaction to a disturbance in Southwark and the ban was surprisingly long. In her book on the Rose playhouse, Carol Chillington Rutter suggests that the Privy Council may not have been reacting only to the riot. The plague season was approaching, a time when large crowds of people could spread disease quickly. The Council may therefore have used the riot as an excuse to set up a ban that they had been planning to announce anyway.

Sure enough, the plague did indeed become a serious problem in the summer of 1592. As a result, the ban on theatre ended up being extended until 29th December. Whatever the reason for it, this was a terrible setback for Philip Henslowe, for Lord Strange's Men and for everyone else involved in the theatres of London. Suddenly, they were all out of work.

So Edward Alleyn, Will Kemp and their team did what actors had always done in the old days: they packed up their gear in wagons and hit the road, touring the country and performing in many different towns and cites. The records of their journey are vague and sporadic, but they appear to have spent June and July in Kent, before travelling west to Bristol in August and then up through the Midlands from September to November. I'll explore this journey in more detail in a future post.

As for Henslowe, we must assume that he arranged to have the Rose boarded up, and started to hunt around for other business opportunities, hoping every day that the ban would be overturned.

As you can see, it is time for this blog to come to a halt, at least until December! But over the next few days, I'll add a few more posts to look back over what we learned.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

|

| The Privy Council in 1604. Detail from The Somerset House Conference |

Concerned about these possible future disturbances, the Privy Council therefore ordered the Mayor of London to "set a strong and substantial watch" about the city. But that was not all. They added that "for avoidance of these unlawful assemblies in these quarters", the Mayor should order

that there be no plays used in any place near thereabouts as the Theatre, Curtain or other usual place where the same are commonly used, nor no other sort of unlawful or forbidden pastimes that draw together the baser sort of people.

This ban on theatre and other gatherings for popular entertainment was to last until "the Feast of St Michael" - that is, 29th September.

|

| London hit by plague, from John Taylor's The Fearful Summer (1636) |

Sure enough, the plague did indeed become a serious problem in the summer of 1592. As a result, the ban on theatre ended up being extended until 29th December. Whatever the reason for it, this was a terrible setback for Philip Henslowe, for Lord Strange's Men and for everyone else involved in the theatres of London. Suddenly, they were all out of work.

|

| St Mary's Guildhall in Coventry, one of the few surviving venues used by Lord Strange's Men during their 1592 tour. |

As for Henslowe, we must assume that he arranged to have the Rose boarded up, and started to hunt around for other business opportunities, hoping every day that the ban would be overturned.

What's next?

As you can see, it is time for this blog to come to a halt, at least until December! But over the next few days, I'll add a few more posts to look back over what we learned.

Further Reading

- Carol Chillington Rutter, Documents of the Rose Playhouse (Manchester University Press, 1984), 62-3

- Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawrence Manley, Lord Strange's Men and their Plays (Yale University Press, 2014), 248-258, 351-2.

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Wednesday, 22 June 2016

22 June, 1592 - A Knack to Know a Knave

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today, Lord Strange's Men revived A Knack to Know a Knave, their new comical morality play; you can read more about it in the entry for 10th June.

This was the company's third performance of A Knack to Know a Knave, but it must have been rather disappointing for them; after the excellent response to the first two shows, the box office today plummeted to below the Rose's average,

But such minor setbacks would soon be out of the company's minds. Tomorrow, their stint at the Rose will come to a sudden end - and so will this blog, at least for a while. Tune in next time to find out why...

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at the knacke to knowe a knave the 22 of June 1592 ... xxvijs

In modern English: Received at The Knack to Know a Knave, 22nd June, 1592 ... 27 shillings

|

| The knaves from an Italian pack of cards, c.1490 |

This was the company's third performance of A Knack to Know a Knave, but it must have been rather disappointing for them; after the excellent response to the first two shows, the box office today plummeted to below the Rose's average,

But such minor setbacks would soon be out of the company's minds. Tomorrow, their stint at the Rose will come to a sudden end - and so will this blog, at least for a while. Tune in next time to find out why...

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Tuesday, 21 June 2016

21 June, 1592 - Tamar Cam

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

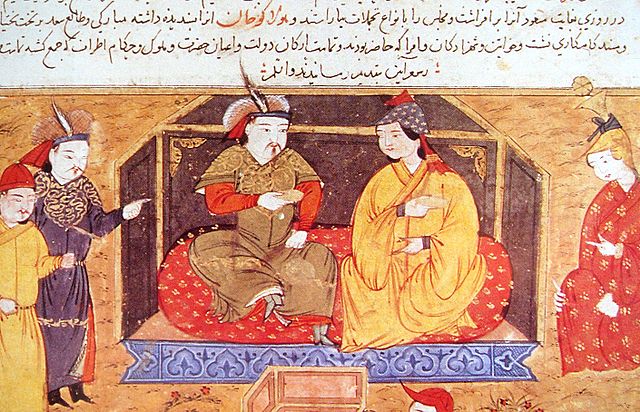

Today, Lord Strange's Men performed one of their plays about Tamar Cam, a lost pair of plays about the Mongol conqueror Hulagu Khan; you can read more about them in the entry for 28th April. As with the previous two performances, we do not know whether this was the first or second part of Tamar Cam; you can read more about this puzzle in the entry for 30th May.

The company had last performed a Tamar Cam play just under two weeks ago. Whichever of the two it was, the play did less well today than on its previous outing, achieving takings that are typical of the average Rose production and represent a half-full theatre.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R atthetambercame the 21 of June 1592 ... xxxijs

In modern English: Received at Tamar Cam, 21st June, 1592 ... 32 shillings

Today, Lord Strange's Men performed one of their plays about Tamar Cam, a lost pair of plays about the Mongol conqueror Hulagu Khan; you can read more about them in the entry for 28th April. As with the previous two performances, we do not know whether this was the first or second part of Tamar Cam; you can read more about this puzzle in the entry for 30th May.

The company had last performed a Tamar Cam play just under two weeks ago. Whichever of the two it was, the play did less well today than on its previous outing, achieving takings that are typical of the average Rose production and represent a half-full theatre.

|

| Persian illustration of Hulagu Khan (the likely inspiration for Tamar Cam) and his Christian wife |

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Monday, 20 June 2016

20 June, 1592 - The Comedy of Hieronimo

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today, Lord Strange's Men gave another performance of The Comedy of Hieronimo, which they had not staged for about a month. This lost play, also known as The Spanish Comedy of Don Horatio, was most likely about the events leading up to those in Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy (you can read more about it in the entry for 23rd February).

The company has now settled into a routine of performing The Spanish Comedy once a month. Today's box office was dismal, representing a mostly empty theatre with an audience of only a quarter of its capacity.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at the comodey of Jeronymo the 20 of June 1592 ... xvs

In modern English: Received at The Comedy of Hieronimo, 20th June, 1592 ... 15 shillings

Today, Lord Strange's Men gave another performance of The Comedy of Hieronimo, which they had not staged for about a month. This lost play, also known as The Spanish Comedy of Don Horatio, was most likely about the events leading up to those in Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy (you can read more about it in the entry for 23rd February).

The company has now settled into a routine of performing The Spanish Comedy once a month. Today's box office was dismal, representing a mostly empty theatre with an audience of only a quarter of its capacity.

- Wednesday, 23rd February - 13 shillings and sixpence (performed as an individual play)

- Monday, 13th March - 29 shillings (performed the day before The Spanish Tragedy)

- Wednesday, 30th March - 39 shillings (performed the day before The Spanish Tragedy)

- Monday, 10th April - 28 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Saturday, 22nd April - 17 shillings (performed one working day before The Spanish Tragedy, but with a Sunday intervening)

- Wednesday, 24th May - 28 shillings (performed the day before The Spanish Tragedy)

- Tuesday, 20th June - 15 shillings (performed as an individual play)

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Sunday, 19 June 2016

19 June, 1592 - Harry VI

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

This play was almost certainly Shakespeare's First Part of Henry VI; you can read more about it in the blog entry for 3rd March.

Lord Strange's Men have returned to performing Harry VI weekly, with no notable change in its box office; it continues to be a merely average performer. It's intriguing that the last four performances have been on Mondays, but I have no explanation for why.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at harey the vj the 19 of June 1592 ... xxxjs

In modern English: Received at Harry VI, 19th June, 1592 ... 31 shillings

|

| 1540s portrait of King Henry VI |

Lord Strange's Men have returned to performing Harry VI weekly, with no notable change in its box office; it continues to be a merely average performer. It's intriguing that the last four performances have been on Mondays, but I have no explanation for why.

- Friday, 3rd March - 75 shillings (premiere)

- Tuesday, 7th March - 60 shillings

- Saturday, 11th March - 47 shillings

- Thursday, 16th March - 31 shillings

- Tuesday, 28th March - 68 shillings (Easter Week)

- Wednesday, 5th April - 41 shillings

- Thursday, 13th April - 26 shillings

- Friday, 21st April - 33 shillings

- Thursday, 4th May - 56 shillings

- Tuesday, 9th May - 22 shillings

- Tuesday, 16th May - 50 shillings (Whitsuntide)

- Monday, 22nd May - 30 shillings

- Monday, 29th May - 24 shillings

- Monday, 12th June - 32 shillings

- Monday, 19th June - 31 shillings

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Labels:

Harry VI,

Other events

Location:

Orléans, France

Friday, 17 June 2016

17 June, 1592 - Hieronimo

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Henslowe appears to have muddled the date again today; I'm going to assume he mistakenly wrote '18' for '17' (since the company would otherwise be skipping Saturday and performing on a Sunday, which would be odd).

Anyway, today, Lord Strange's Men revived Hieronimo, which is almost certainly an alternate title for Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy. You can read more about this play in the entry for 14th March.

The company had last performed this play just over a week ago. Its box office continues to be weak, but the company still seems to find it worth their while to perform it very frequently.

There will be no entry tomorrow because 18th June was a Sunday in 1592. Henslowe's Diary ... as a Blog! will thus return on 19th June for a week in which this season at the Rose will end abruptly and unexpectedly.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at Jeronymo the 18 of June 1592 ... xxiiijs

In modern English: Received at Hieronimo, 17th June, 1592 ... 24 shillings

Henslowe appears to have muddled the date again today; I'm going to assume he mistakenly wrote '18' for '17' (since the company would otherwise be skipping Saturday and performing on a Sunday, which would be odd).

|

| Woodcut from the 1615 edition of The Spanish Tragedy. |

The company had last performed this play just over a week ago. Its box office continues to be weak, but the company still seems to find it worth their while to perform it very frequently.

- Tuesday, 14th March - 71 shillings (performed the day after the Comedy)

- Monday, 20th March - 38 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Friday, 31st March - 60 shillings (Easter Week; performed the day after the Comedy)

- Friday, 7th April - 26 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Friday, 14th April - 33 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Monday, 24th April - 28 shillings (performed one working day after the Comedy, but with Sunday interrupting)

- Tuesday, 2nd May - 34 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Thursday, 11th May - 26 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Monday, 15th May - 64 shillings (Whitsuntide; performed as an individual play)

- Thursday, 25th May - 27 shillings (performed the day after the Comedy)

- Wednesday, 31st May - 23 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Friday, 9th June - 28 shillings (performed as an individual play)

- Saturday, 17th June - 24 shillings (performed as an individual play)

What's next?

There will be no entry tomorrow because 18th June was a Sunday in 1592. Henslowe's Diary ... as a Blog! will thus return on 19th June for a week in which this season at the Rose will end abruptly and unexpectedly.

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Thursday, 16 June 2016

16 June, 1592 - Sir John Mandeville

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today, Lord Strange's Men decided to revive their lost play about Sir John Mandeville, which they had last performed a month ago. Although Mandeville is today most famous for his fantastical travel narratives, the most plausible theory is that this play was a chivalric and comic romance, in which Sir John won the hand of a fair lady above his station; you can read more about the play in the entry for 24th February.

Sir John Mandeville normally receives mediocre box office and today was no exception, being well below the average for a Rose play.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at mandevell the 16 of June 1592 ... xxs

In modern English: Received at Mandeville, 16th June, 1592 ... 20 shillings

|

Mandevillian monster from

the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493)

|

Sir John Mandeville normally receives mediocre box office and today was no exception, being well below the average for a Rose play.

- Thursday, 24th February - 12 shillings

- Saturday, 1st April - 30 shillings

- Saturday, 15th April - 26 shillings

- Thursday, 18th May (Whitsuntide festival) - 40 shillings

- Friday, 16th June - 20 shillings

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Wednesday, 15 June 2016

15 June, 1592 - A Knack to Know a Knave

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today, Lord Strange's Men revived A Knack to Know a Knave, their new comical morality play; you can read more about it in the entry for 10th June.

The company had premiered Knack only 6 days ago, to great success, and were clearly keen to stage it again as soon as possible. Today's performance received a handsome 52 shillings, way above the Rose average, and thus following the usual pattern in which new plays tended to perform strongly in their first few stagings.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at the knacke to knowe a knave the 15 of June 1592 ... lijs

In modern English: Received at The Knack to Know a Knave, 15th June, 1592 ... 52 shillings

|

| The knaves from an Italian pack of cards, c.1490 |

The company had premiered Knack only 6 days ago, to great success, and were clearly keen to stage it again as soon as possible. Today's performance received a handsome 52 shillings, way above the Rose average, and thus following the usual pattern in which new plays tended to perform strongly in their first few stagings.

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Tuesday, 14 June 2016

14th June, 1592 - The Jew of Malta

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today, Lord Strange's Men performed their satirical comic tragedy The Jew of Malta again, which they had last performed just under a fortnight ago. You can read more about this play in the blog entry for 26th February.

The company has returned to its practice of performing The Jew of Malta once a fortnight, and it has produced a slightly above average box office today.

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at the Jewe of malta the 14 of June 1592 ... xxxviijs

In modern English: Received at The Jew of Malta, 14th June, 1592 ... 38 shillings

.jpg/700px-Portrait_of_Alof_de_Wignacourt_and_his_Page-Caravaggio_(1607-1608).jpg) |

Caravaggio's portrait of the Grand

Master of the Knights of Malta,

1607-8.

|

The company has returned to its practice of performing The Jew of Malta once a fortnight, and it has produced a slightly above average box office today.

- Saturday, 26th February - 50 shillings

- Friday, 10th March - 56 shillings

- Saturday, 18th March - 39 shillings

- Tuesday, 4th April, 43 shillings

- Tuesday, 18th April, 48 shillings and sixpence

- Friday, 5th May, 41 shillings

- Saturday, 13th May, 34 shillings

- Tuesday, 23rd May, 54 shillings

- Friday, 2nd June, 33 shillings

- Wednesday, 14th June, 38 shillings

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Monday, 13 June 2016

13th June, 1592 - Muly Molocco

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today, Lord Strange's Men returned again to Muly Molocco, which they had last performed a week and a half ago. This play was about Abd el-Malik's struggle for the throne of Morocco; you can read more about it in the blog entry for 21st February.

The company continues to perform Muly Molocco every ten days or so. Normally, the play produces reliably average box office, but the last two performances have seen a notable slump toward the lower end of the spectrum. Is this just a blip or is Muly Molocco on the way out?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: R at mvlemvloco the 13 of June 1592 ... xxs

In modern English: Received at Muly Molocco, 13th June, 1592 ... 20 shillings

|

| 1629 Portuguese illustration of the Battle of Alcazar |

The company continues to perform Muly Molocco every ten days or so. Normally, the play produces reliably average box office, but the last two performances have seen a notable slump toward the lower end of the spectrum. Is this just a blip or is Muly Molocco on the way out?

- Monday, 21st February - 29 shillings

- Tuesday, 29th February - 34 shillings

- Friday, 17th March - 29 shillings

- Wednesday, 29th March - 62 shillings

- Saturday, 8th April - 23 shillings

- Monday, 17th April - 30 shillings

- Thursday, 27th April - 26 shillings

- Monday, 1st May - 58 shillings

- Friday, 19th May - 36 shillings

- Saturday, 3rd June - 24 shillings

- Tuesday, 13th June - 20 shillings

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Sunday, 12 June 2016

12 June 1592 - Harry VI (and a riot)

A great disorder and tumult

|

| Making a felt hat, 1568. |

being informed of a great disorder and tumult like to grow yesternight about 8 of the clock within the borough of Southwark, I went thither with all speed I could, taking with me one of the sherriffs, where I found great multitudes of people assembled together and the principal actors to be certain apprentices of the feltmakers gathered together out of Barmsey Street and the Blackfriars with a great number of loose and masterless men apt for such purposes.

Webbe learned that the apprentices were rioting because a feltmonger's servant had been wrongly imprisoned. He arrested the "doers and authors of the disorder" and asked Burghley if there was anything more that he could do.

You may be wondering what this has to do with the Rose playhouse, but because the apprentices had made "pretense of their meeting at a play" (apparently on a Sunday, although this was against the law), Webbe grumbled in his letter that plays "giveth opportunity of committing these and suchlike disorders". It will take a couple of weeks for the authorities to respond, but when they do it will be with draconian measures that will not only crack down on public disorder but will also be catastrophic for the Rose and the other theatres. More on that later...

The play

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Henslowe writes: R at harey the vj the 12 of June 1592 ... xxxijs

In modern English: Received at Harry VI, 12th June, 1592 ... 32 shillings

|

| 1540s portrait of King Henry VI |

- Friday, 3rd March - 75 shillings (premiere)

- Tuesday, 7th March - 60 shillings

- Saturday, 11th March - 47 shillings

- Thursday, 16th March - 31 shillings

- Tuesday, 28th March - 68 shillings (Easter Week)

- Wednesday, 5th April - 41 shillings

- Thursday, 13th April - 26 shillings

- Friday, 21st April - 33 shillings

- Thursday, 4th May - 56 shillings

- Tuesday, 9th May - 22 shillings

- Tuesday, 16th May - 50 shillings (Whitsuntide)

- Monday, 22nd May - 30 shillings

- Monday, 29th May - 24 shillings

- Monday, 12th June - 32 shillings

FURTHER READING

The riot

- Carol Chillington Rutter, Documents of the Rose Playhouse (Manchester University Press, 1984), 61-2

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Labels:

Harry VI

Friday, 10 June 2016

10 June, 1592 - A Knack to Know a Knave

Here's what Lord Strange's Men performed at the Rose playhouse on this day, 424 years ago...

Today was an exciting day at the Rose playhouse, as Lord Strange's Men premiered a new play! A Knack to Know a Knave is a rather daft moral fable about the unmasking of devious tricksters. As we have seen, debut performances of new plays are always very popular at the Rose, but this one was at the higher end of the spectrum, being in the same league as Harry VI and The Tanner of Denmark, whose premieres appear to have filled the theatre to capacity. After the mysterious premiere of The Tanner of Denmark, which they never performed again, the company must have been keen for this new play to be a more straightforward hit.

What made A Knack to Know a Knave so popular? When it was first published, in 1594, its title page described it as follows:

The play itself reads as though it is trying to please everyone, as it fuses a number of genres from the repertory of Lord Strange's Men. At essence, it is a morality play like A Looking Glass for London: it preaches against dishonest behaviour by depicting the downfall of four knaves. But it adds another storyline about a king who falls in love with a country woman and receives assistance from a necromantic friar, a tale that is reminiscent of Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. And a lot of the dialogue is filled with the 'high astounding terms' popularized by Christopher Marlowe: grand speeches full of classical allusions and exotic place names, as in Muly Molocco. In addition, there's a scene of comedy rustic yokels for good measure. So, if you didn't like anything in A Knack to Know a Knave, you probably didn't like theatre.

Unfortunately, despite this entertaining content, the surviving playtext is not an easy read. It's full of weird grammar and awkward verse, and some scenes seem condensed to the point of incomprehensibility. For these reasons, most scholars think the text is a 'memorial reconstruction' - that is, it was put together by actors who were recalling (or half-recalling) their lines from performances of the play.

Still, A Knack to Know a Knave is a vivid glimpse of just how weird and wonderful the popular Elizabethan theatre could be. Let's look more closely at how it works...

A Knack to Know a Knave is set in 10th century England, during the reign of King Edgar. The King asks an allegorical figure named Honesty to expose all the knavery in his kingdom.

One source of knavery is the nasty old bailiff of Hexham, who has four knavish sons (presumably an allusion to the four knaves in a pack of cards). On his death bed, the bailiff gives a final word of advice to his sons, telling them to live by pure selfishness and don't be afraid of Hell:

Immediately after he says this, the old man dies and realizes that he is "damned to ever-burning fire" when a devil enters and carries him away. But the sons are unfazed and resolve to follow their father's advice.

The four sons occupy different social positions, but each of them exploits the weak by using deceit. Cuthbert the coney-catcher (con-artist) uses falsehoods to steal a farm. Perin the courtier deceives people by misusing the royal seal. Walter the farmer oppresses his neighbours and sells corn to the enemy. And John the puritanical priest avoids giving charity. The play thus belongs to the genre known as 'estate satire', which criticizes wrongdoing at every level of society; the brothers represent city, country, court and church respectively.

Over the course of the play, Honesty exposes all of the brothers' lies. You might think that an allegorical figure named Honesty might be kind and forgiving even to the worst villains, but no: he sentences them to hideous punishments. Cuthbert the coney-catcher is to have his tongue pinned to his chest and must stand in the marketplace as a spectacle until birds peck his eyes out. Walter the farmer, who loved corn too much, is sentenced to have his limbs cut off and to be left in a cornfield where crows will peck out his eyes. Perin the courtier will be humiliated by being hanged at Tyburn with a cheap rope, like a commoner. And John the priest will be taken to Finsbury Fields and shot. This may seem a little drastic, but, as Honesty explains to the audience, "I warn you all that use such subtle villainy, / Beware that you like these be found by Honesty". It's not a comforting play.

The story of the four knaves is interwoven with another tale about dishonesty. King Edgar hears of a beautiful maid named Alfrida. Ashamed to woo her himself, he sends a lord, Ethenwald, to woo her by proxy, but Ethenwald falls in love with Alfrida himself and marries her, telling the king that she turned out to be too ugly to be suitable to a monarch.

When the King decides to visit the couple, Ethenwald fears that he will steal Alfrida from him, and persuades her to swap identities with the kitchen maid. When the King learns what they have done - committing yet another act of dishonesty - he angrily decides to murder Ethenwald. Bishop Dunstan, a wizardly friar who advises the King, fears that he is turning into a tyrant and summons a devil to convince him not to.

Exactly how the devil changes the King's mind is unclear, and it's an example of the messiness of the surviving text. The King insists, "I will never pardon Ethenwald!" Dunstan summons the devil Asmeroth, and "Here enter Alfrida disguised with the Devil". The King asks incredulously "Is this Alfrida?" and Dunstan tells him it is, and "This is Ethenwald, / That lays his breast wide open to your grace". The King pardons Alfrida and Ethenwald, and all are happy. This doesn't make any sense. What changed the King's mind? What exactly did the devil do? And where did Ethenwald come from? There seem to be missing stage directions and the whole thing is a bit baffling.

which in legend was inhabited by fools. Presumably, the great comic actor Will Kemp had the audience in stitches during this scene. But you'd never know it from the short and unfunny scrap of dialogue that survives.

The yokels of Gotham exchange some dimwitted conversation ("Now let us constult among ourselves" says one). Then the King passes by and the Gothamites present him with a petition, which requests "nothing but to have a license to brew strong ale thrice a week, and he that comes to Gotham and will not spend a penny on a pot of ale, if he be a-dry, that he may fast". You might expect some banter between King and commoners about this petition, but the King simply says "Well sirs, we grant your petition," and off he goes. Hilarious.

I think you probably had to be there to understand why this was funny. But that's precisely the point. As a comic performer, Will Kemp specialized in improvisation rather than following a set script, so we can image that this rather flat little scene was merely a launch pad for Kemp and his sidekicks to riff from and to spin out in whatever way amused their audience most.

As you can see, A Knack to Know a Knave was probably great fun on stage but is not a very pleasurable read. This applies equally well to the last lines, in which Honesty asks (in rather clunky verse) the audience to reward them with applause:

If you really want to read A Knack to Know a Knave, you can look at this Victorian edition from John Payne Collier's Five Old Plays (1851).

We learn from A Knack to Know a Knave that sometimes you lose a great deal from these plays if you didn't see them in the Rose playhouse in the 1590s. Indeed, Knack seems aimed very directly at theatregoers of that specific time, because it is packed with reminders of other popular plays that the audience would have known. Here are just three examples.

At one point, King Edgar compares himself to "wise Vespasian, Rome's rich emperor". This would remind the Rose's regular audience of Titus and Vespasian, which had been popular with the crowds in recent months. Later, when an old man praises King Edgar's unbiased application of justice, he compares him to "Vespasian, Rome's virtuous emperor, / Who for a blow his son did give a swain [i.e. a peasant] / Did straight command that he should lose his hand." Perhaps this line actually describes a scene in the lost play of Titus and Vespasian; if so, you can imagine the audience nodding as they remember it.

When the Bailiff of Hexham is carried away by a devil into Hell, the audience was seeing replayed a popular stage tradition that went back to the Middle Ages. If the bailiff's death was played comically, it might remind them of the demise of Miles in Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, or if it was performed more seriously, it might recall the tragic ending of Dr Faustus, which was then being performed by a company at a different theatre.

And in another scene, Alfrida's father invites King Edgar into his house, saying

So, if you were a keen theatregoer in 1592, you might have enjoyed the way A Knack to Know a Knave creates a sense of community in the theatre by building on the shared knowledge of its audience.

There will be no blog entry tomorrow because 11th June was a Sunday in 1592. Henslowe's Diary ... a a Blog! will thus return on 12th June with another play - and with something more ominous...

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

Henslowe writes: ne ... R at a knacke to knowe a knave 1592 10day ... iijll xijs

In modern English: New. Received at A Knack to Know a Knave, 1592, 10th day [of June] ... £3 and 12 shillings

Today was an exciting day at the Rose playhouse, as Lord Strange's Men premiered a new play! A Knack to Know a Knave is a rather daft moral fable about the unmasking of devious tricksters. As we have seen, debut performances of new plays are always very popular at the Rose, but this one was at the higher end of the spectrum, being in the same league as Harry VI and The Tanner of Denmark, whose premieres appear to have filled the theatre to capacity. After the mysterious premiere of The Tanner of Denmark, which they never performed again, the company must have been keen for this new play to be a more straightforward hit.

The play

|

| The 1594 publication of A Knack to Know a Knave |

A most pleasant and merry new comedy entitled A Knack to Know a Knave, newly set forth as it hath sundry times been played by Ed. Alleyn and his company; with Kemp's applauded merriments of the men of Gotham in receiving the King into Gotham.This description is not very informative about the play's content, as the scene involving the "men of Gotham" is only a tiny part of it. Instead, this title page appeals to fans of Edward Alleyn and Will Kemp, the stars of Lord Strange's Men, treating them as guarantees of quality.

The play itself reads as though it is trying to please everyone, as it fuses a number of genres from the repertory of Lord Strange's Men. At essence, it is a morality play like A Looking Glass for London: it preaches against dishonest behaviour by depicting the downfall of four knaves. But it adds another storyline about a king who falls in love with a country woman and receives assistance from a necromantic friar, a tale that is reminiscent of Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. And a lot of the dialogue is filled with the 'high astounding terms' popularized by Christopher Marlowe: grand speeches full of classical allusions and exotic place names, as in Muly Molocco. In addition, there's a scene of comedy rustic yokels for good measure. So, if you didn't like anything in A Knack to Know a Knave, you probably didn't like theatre.

Unfortunately, despite this entertaining content, the surviving playtext is not an easy read. It's full of weird grammar and awkward verse, and some scenes seem condensed to the point of incomprehensibility. For these reasons, most scholars think the text is a 'memorial reconstruction' - that is, it was put together by actors who were recalling (or half-recalling) their lines from performances of the play.

Still, A Knack to Know a Knave is a vivid glimpse of just how weird and wonderful the popular Elizabethan theatre could be. Let's look more closely at how it works...

The knaves

A Knack to Know a Knave is set in 10th century England, during the reign of King Edgar. The King asks an allegorical figure named Honesty to expose all the knavery in his kingdom.

|

| The knaves from an Italian pack of cards, c.1490 |

Carve to yourselves and care not what they say

That bid you fear the fearful Judgement Day:

Live to yourselves while you have time to live,

Get what you can, but see you nothing give.

Immediately after he says this, the old man dies and realizes that he is "damned to ever-burning fire" when a devil enters and carries him away. But the sons are unfazed and resolve to follow their father's advice.

|

| Image from A Quip for an Upstart Courtier (1592), a prose example of 'estate satire', |

Over the course of the play, Honesty exposes all of the brothers' lies. You might think that an allegorical figure named Honesty might be kind and forgiving even to the worst villains, but no: he sentences them to hideous punishments. Cuthbert the coney-catcher is to have his tongue pinned to his chest and must stand in the marketplace as a spectacle until birds peck his eyes out. Walter the farmer, who loved corn too much, is sentenced to have his limbs cut off and to be left in a cornfield where crows will peck out his eyes. Perin the courtier will be humiliated by being hanged at Tyburn with a cheap rope, like a commoner. And John the priest will be taken to Finsbury Fields and shot. This may seem a little drastic, but, as Honesty explains to the audience, "I warn you all that use such subtle villainy, / Beware that you like these be found by Honesty". It's not a comforting play.

King Edgar and the fair maid

|

| King Edgar illustrated in 966; from BL Cotton Vespasian A viii |

When the King decides to visit the couple, Ethenwald fears that he will steal Alfrida from him, and persuades her to swap identities with the kitchen maid. When the King learns what they have done - committing yet another act of dishonesty - he angrily decides to murder Ethenwald. Bishop Dunstan, a wizardly friar who advises the King, fears that he is turning into a tyrant and summons a devil to convince him not to.

Exactly how the devil changes the King's mind is unclear, and it's an example of the messiness of the surviving text. The King insists, "I will never pardon Ethenwald!" Dunstan summons the devil Asmeroth, and "Here enter Alfrida disguised with the Devil". The King asks incredulously "Is this Alfrida?" and Dunstan tells him it is, and "This is Ethenwald, / That lays his breast wide open to your grace". The King pardons Alfrida and Ethenwald, and all are happy. This doesn't make any sense. What changed the King's mind? What exactly did the devil do? And where did Ethenwald come from? There seem to be missing stage directions and the whole thing is a bit baffling.

The mad men of Gotham

which in legend was inhabited by fools. Presumably, the great comic actor Will Kemp had the audience in stitches during this scene. But you'd never know it from the short and unfunny scrap of dialogue that survives.

The yokels of Gotham exchange some dimwitted conversation ("Now let us constult among ourselves" says one). Then the King passes by and the Gothamites present him with a petition, which requests "nothing but to have a license to brew strong ale thrice a week, and he that comes to Gotham and will not spend a penny on a pot of ale, if he be a-dry, that he may fast". You might expect some banter between King and commoners about this petition, but the King simply says "Well sirs, we grant your petition," and off he goes. Hilarious.

I think you probably had to be there to understand why this was funny. But that's precisely the point. As a comic performer, Will Kemp specialized in improvisation rather than following a set script, so we can image that this rather flat little scene was merely a launch pad for Kemp and his sidekicks to riff from and to spin out in whatever way amused their audience most.

Weigh it as it is

As you can see, A Knack to Know a Knave was probably great fun on stage but is not a very pleasurable read. This applies equally well to the last lines, in which Honesty asks (in rather clunky verse) the audience to reward them with applause:

And thus, though long at last we make an end,

Desiring you to pardon what's amiss

And weigh the work though it be grossly penned;

Laugh at the faults and weigh it as it is

And Honesty will pray upon his knee:

God cut them off that wrong the Prince or commonality

And may her days of bless never have end

Upon whose life so many lives depend.

If you really want to read A Knack to Know a Knave, you can look at this Victorian edition from John Payne Collier's Five Old Plays (1851).

What we learn from this

We learn from A Knack to Know a Knave that sometimes you lose a great deal from these plays if you didn't see them in the Rose playhouse in the 1590s. Indeed, Knack seems aimed very directly at theatregoers of that specific time, because it is packed with reminders of other popular plays that the audience would have known. Here are just three examples.

At one point, King Edgar compares himself to "wise Vespasian, Rome's rich emperor". This would remind the Rose's regular audience of Titus and Vespasian, which had been popular with the crowds in recent months. Later, when an old man praises King Edgar's unbiased application of justice, he compares him to "Vespasian, Rome's virtuous emperor, / Who for a blow his son did give a swain [i.e. a peasant] / Did straight command that he should lose his hand." Perhaps this line actually describes a scene in the lost play of Titus and Vespasian; if so, you can imagine the audience nodding as they remember it.