Henslowe writes: R at the lookinglasse the 8 of marche 1591 ... vijs

In modern English: Received at The Looking-Glass, 8th March 1592 ... 7 shillings

Today Lord Strange's Men performed A Looking-Glass for London and England by Robert Greene and Thomas Lodge (we've already met Greene as the author of Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay and Orlando Furioso). The play is a Biblical tale about the sins of the city of Nineveh; its title means 'this play is a mirror in which London and England may see themselves'.

|

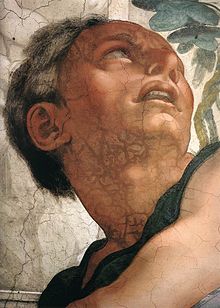

| Michelangelo's Jonah, from the Sistine Chapel |

In adapting this story, Greene and Lodge broaden the scope of the Biblical text (which is short and focused almost entirely on Jonah's experience) to create a spectacular depiction of the inhabitants of this city of sin, repeatedly drawing attention to its parallels with London. The play features a range of impressive special effects, and I've quoted a number of its wonderful stage directions in the summary below.

The story and the spectacle

A Looking-Glass for London and England is set in the city of Nineveh, a disgusting sink of vice and sin. To it, an angel brings the prophet Hosea who is "set down over the stage in a throne", from which he watches and comments on the entire action of the play, occasionally pointing out to the audience its relevance to modern England ("London, take heed, these sins abound in thee!").

The sins of Nineveh, and God's repeated warnings to its people, are depicted at all levels of society. The king, Rasni, is an egomaniac who revels in pomp and luxury and wants to marry his own sister, but when she is blasted by a lightning bolt ("he finds her strucken with thunder, black"), Rasni ignores the warning and takes the lecherous murderess Alvida as his lover instead.

Rasni's flattering adviser, Radagon, is so ambitious that he refuses to help his own family, who are starving because a usurer has cheated them. Radagon's mother curses him, and "a flame of fire appeareth from beneath and Radagon is swallowed". But the court of Nineveh still doesn't take the hint, dismissing it as a natural phenomenon.

Meanwhile, among the underclass, Adam the clown (presumably played by the comic actor Will Kemp) is a smith's man who is found drunk next to a corpse (killed by someone else in a drunken quarrel). Fortunately for him, King Rasni considers crimes committed by drunks to be unworthy of interest and takes no action.

That's the kind of thing that goes on in Nineveh every day, so something needs to be done! In the middle of the play, an angel tells Jonah to go to Nineveh and preach against its sinfulness. Jonah refuses and instead takes ship to Tharsus.

|

| Jonah and the Whale by Pieter Lastman (1621) |

When Jonah arrives in Nineveh and prophesies its destruction, King Rasni orders forty days of penance and the entire city fasts and dons sackcloth. Adam doesn't obey the order to fast, and is taken away to be hanged.

|

| Maarten van Heemskerck, Jonah Contemplates Nineveh (1566) |

At the end of the play, Jonah informs the audience that London too must repent. While he's about it, he manages to praise Queen Elizabeth and bash Catholicism too:

Oh turn, oh turn, with weeping to the Lord,

And think the prayers and virtues of thy Queen

Defers the plague which otherwise would fall.

Repent, oh London, lest for thine offence

Thy shepherd fail (whom mighty god preserve

That she may bide the pillar of His church

Against the storms of Romish Antichrist!).

The hand of mercy overshade her head

And let all faithful subjects say 'Amen'.

If you would like to read A Looking-Glass for London and England, there are old-spelling editions with useful introductions by J. Churton Collins' (in The Plays and Poems of Robert Greene, 1905) or by George Allan Clugston (published by Garland in 1980).

What we learn from this

A Looking-Glass for London and England is more overtly moralistic than the other plays that we've seen so far. Looked at it in the context of the other plays we've seen, it feels rather hypocritical of the players to perform such a finger-wagging play so soon after the amoral bawdy fun of Bindo and Ricciardo and the complex religious satire of The Jew of Malta. And its dismal financial returns (a paltry 7 shillings, by far the worst box office of any play so far) implies that London did not want to be lectured about its sins.

When you think of this play being performed to a mostly empty theatre, its spectacular stage directions read rather sadly; populist effects such as lightning blasts, firey deaths and whale's mouths may have felt rather hollow when deployed to entertain only a small huddle of spectators. When one adds the constant berating of the immorality of Londoners, one cannot help but feel that the atmosphere in the Rose this day may have been rather awkward and embarrassing.

FURTHER READING

A Looking-Glass for London and England information

- The Plays and Poems of Robert Greene, ed. J. Churton Collins (Clarendon Press, 1905), 1:137-42.

- Martin Wiggins, British Drama, 1533-1642: A Catalogue, vol. 2 (Oxford University Press, 2012), entry 829.

- Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawrence Manley, Lord Strange's Men and their Plays (Yale University Press, 2014), 101-3.

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

No comments:

Post a Comment