Henslowe writes: ne ... R at the seconde pte of tamber came the 28 aprell ... 3ll iiijs

In modern English: New. Received at The Second Part of Tamar Cam, 28th April ... £3 and 4 shillings

Today, Lord Strange's Men unveiled a brand new play: The Second Part of Tamar Cam. Just like the previous two premieres - those of Harry VI and Titus and Vespasian - this one resulted in excellent box office: 64 shillings, indicating (perhaps) an almost full theatre.

The Second Part of Tamar Cam is yet another lost play that was never published. However, it is possible to reconstruct its likely subject matter. That's because The First Part of Tamar Cam partially survives in outline form, and indicates that the two plays were about the thirteenth century Mongol warlord Hulagu Khan and his conquest of the Middle East. Hulagu Khan may not be a familiar name today, but there were good reasons why a play about him could have enticed large numbers of Elizabethan Londoners to the theatre. Let's take a step-by-step look at the process of reconstructing this play...

1. The 'plot' of Tamar Cam 1

The Second Part of Tamar Cam is entirely lost, but its predecessor partially survives via a transcript of a rare surviving document from the Elizabethan theatre known as a 'plot'. 'Plots' were tables listing the entrances and exits for each scene of a play; these documents were apparently used backstage to assist in organising the productions. You can see a transcript of the 'plot' of The First Part of Tamar Cam here (thanks to the Lost Plays Database). The 'plot' does not tell us exactly what happened in The First Part, but it does tell us the names of its characters and shows us the various configurations in which they appeared during the play.

A glance at the 'plot' of The First Part reveals that it was a play about Mongol conquerors ('Cam' or 'Cham' is a common Elizabethan rendering of the title 'Khan'), and that it involved Persia, princesses, beheadings, and the summoning of magical spirits.

2. Channelling Tamburlaine

|

| Illustration of the historical Tamburlaine from Richard Knolles' General History of the Turks (1603). |

We can't know exactly how similar the plays were. The 'plot' of The First Part of Tamar Cam shows that it contained black magic and magical spirits, which are absent from Marlowe's play. But it certainly attempted to mimic the exoticism of Tamburlaine: it climaxed with a parade of foreign peoples, including Tartars, Amazons, "olive coloured Moors", cannibals, hermaphrodites, "the people of Bohare", pygmies, Crimeans, and Bactrians. This must have been an incredible spectacle and seems to be echoing the epic, global panorama that Tamburlaine conjured so memorably.

3. Identifying Tamar Cam

So, who was 'Tamar Cam'? W.W. Greg proposed that the name likely referred to Temuchin, better known as Genghis Khan, since he was by far the most famous of the Mongol conquerors. However, Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawence Manley's detailed study of the evidence demonstrates that the play was more likely about one of Genghis Khan's descendants.

The 'plot' of The First Part refers to one 'Mango Cam', who is presumably Möngke Khan, Genghis's grandson and fourth emperor of the Mongol Empire. If so, then the titular 'Tamar Cam' would be the approximately contemporary Temür Khan, who became the sixth emperor. However, Temür's career had nothing to do with Persia, which appears so prominently in the 'plot'. MacLean and Manley propose therefore that the playwright took Temür's name only, and in fact told the story of Möngke's brother, Hulagu Khan, who was sent west to conquer Persia. The reason they changed the names is, no doubt, simply because 'Tamar Cam' sounds similar to 'Tamburlaine'.

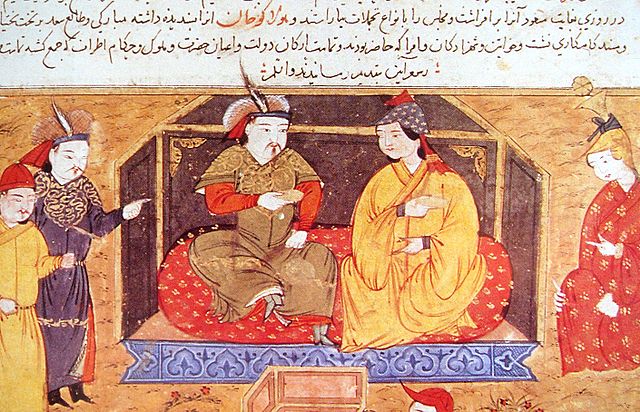

|

| Persian illustration of Hulagu Khan (the likely inspiration for Tamar Cam) and his Christian wife |

Mango the great Khan of Tartary ... sent his brother Haalon with an exceeding great army against the Turks and Saracens in Syria and the land of Palestine. This Haalon, converted also unto the Christian faith by his wife, setting forward with a world of people following him, in the space of six months overran all Persia, with the countries adjoining.

4. Triumph or tragedy?

So, how exactly did the dramatist tell the story of Hulagu Khan? As far as we can tell from the hard-to-decipher 'plot', The First Part appears to have mostly been about Tamar Cam choosing the Christian princess Palmida over a Persian princess; there were also battles, a conspiracy against Tamar, and helpful spirits on both sides of the conflict, as well as a clown. The story of The Second Part is less knowable, but after Persia, the historical Hulagu went on to conquer Baghdad and Aleppo, so perhaps the sequel concerned itself with that.

|

| From a 15th century French edition of Marco Polo: Hulagu (on the left) orders the imprisonment of the Caliph of Baghdad in his own treasure-vault to starve. |

However, as we've seen in Muly Molocco and The Jew of Malta, the Middle Eastern plays of the Rose were not always straightforward 'us versus them' narratives, and Tamburlaine is a defiantly un-Christian play, in which the title character spurns all gods and ultimately dies after burning, not the Bible, but the Qu'ran. And Tamar Cam could have ended on a more challenging note too. MacLean and Manley note that the historical sources record a potential downbeat ending in which Tamar's achievements are undermined by Christian intolerance: as Knolles tells it, Hulagu's successor, angered by a quarrel with Dutch soldiers over captured booty, repudiated Christianity and "he and his Tartars became utter enemies unto the Christians, doing them all the harm they could devise", an outcome that Knolles blames on "the insolency of certain Christian soldiers". If The Second Part of Tamar Cam ended this way, it would have been somewhat more like Tamburlaine, which ends with the unravelling of the title character's empire.

Whatever the exact plot and tone of The Second Part of Tamar Cam, its debut performance was a great success, making just as much money as Titus and Vespasian's premiere, although still not achieving the heights of Harry VI's. Lord Strange's Men had another blockbuster on their hands, and once again they had done so by riffing on older plays.

Further reading

Tamar Cam information

- Richard Knolles, The General History of the Turks (1603), 113-14.

- Thomas Fuller, The History of the Holy War (1639), 208.

- W.W. Greg, Dramatic Documents from the Elizabethan Playhouse (Clarendon Press, 1931)

- Martin Wiggins, British Drama, 1533-1642: A Catalogue, vol. 3 (Oxford University Press, 2013), entries 906 and 925.

- Sally-Beth MacLean and Lawrence Manley, Lord Strange's Men and their Plays (Yale University Press, 2014), 138-43.

- David McInnis, "Tamar Cham, Parts 1 and 2", Lost Plays Database (2016).

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

No comments:

Post a Comment