Henslowe writes: ye 9 of June 1594 ... R at hamlet ... viijs

In modern English: 11th June, 1594 ... Received at Hamlet ... 8 shillings.

Well, here's a surprise! Today, Hamlet, one of the most famous plays of the English Renaissance, was performed at Newington Butts. But as always with Henslowe's Diary, things are more complicated than they seem. Shakespeare's Hamlet is normally dated to circa 1600, so what is it doing here 6 years previously?

The answer is that today's play was probably not the Hamlet that we know today. Shakespeare did not invent the story of Prince Hamlet: it is based on a Scandinavian legend, retold in many forms over the centuries, in which a young man fakes madness in order to exact revenge upon the murderer of his father. So, this play may be an older, lost dramatization of the story (rather like the early King Leir play that we saw in April).

Scholars call this hypothetical lost play "the ur-Hamlet". Let's go through exactly what we know about this early Hamlet and the intriguing question of who wrote it.

1. Thomas Nashe and the English Senecas

In 1589, the satirist Thomas Nashe wrote the preface to a prose tale called Menaphon by his friend, the playwright Robert Greene. In it, Nashe writes facetiously about English writers who attempt to imitate ancient Roman authors. In particular, he refers to a fashion for emulating Seneca, a Roman dramatist whose tragedies are known for their long, rhetorical speeches and gruesome horrors.

|

| Seneca's Ten Tragedies Translated into English (1581), an example of the vogue for Senecan drama |

This is not a very funny joke. But what's important is that Nashe gratuitously brings the word 'Hamlet' into a discussion of English Senecan tragedies. This implies that a play about Hamlet already existed, and that it was in the Senecan mode.

Was this early Hamlet written by the young William Shakespeare? We simply don't know, because the historical record tells us nothing about what Shakespeare was doing in the late 1580s.

Nashe hints at an alternative author. Continuing to scoff at Seneca's English followers, he says they "imitate the Kid in Aesop, who, enamoured with the Fox's newfangles, forsook all hopes of life to leap into a new occupation". This refers to Aesop's fable of the Fox and the Goat, but Nashe's use of the word "Kid" to refer to the foolish animal could be a pun on the playwright Thomas Kyd. After all, Kyd's Spanish Tragedy, one of the most popular plays at the Rose, is a perfect example of a Senecan tragedy, and shares several plot elements with Hamlet. So could Nashe be jokingly referring to Kyd as the author of the Hamlet play too? We don't know.

2. Henslowe's diary

Five years later, we find today's entry in Henslowe's Diary: a performance of Hamlet at Newington Butts. Is this the same play that Nashe was referring to? Probably, since Henslowe does not label it as new.

In other words, in 1594, Shakespeare was probably acting in an old play called Hamlet. Was he its author? Or was he inspired by it to write his own version of the story? We don't know.

3. Thomas Lodge and the miserable ghost

Two years later, in 1596, Thomas Lodge wrote a satirical piece entitled Wit's Misery in which he categorized the devils who lurk around London. One devil is called 'Hate-Virtue' and Lodge describes him thus: he "looks as pale as the vizard of the ghost which cried so miserably at the Theatre, like an oyster-wife, 'Hamlet, revenge!'".

|

| Henry Fuseli's illustration of the ghost calling Hamlet to revenge (1796) |

The line "Hamlet, revenge!" does not appear in this exact form in any surviving version Shakespeare's play, and may thus hint at the existence of an earlier version. Overall, Lodge's comments could suggest that Shakespeare's company was still performing an old Hamlet play in 1596.

4. Hamlet by Shakespeare

|

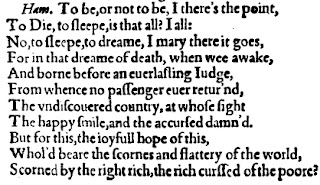

| An unfamiliar version of the "To be or not to be" speech from the Q1 version of Hamlet |

Then, in 1604 and in 1623, two more texts were published; despite some differences between them, they together represent the play that we think of as Hamlet.

None of these texts read as though they were written in the 1580s, and a lot of internal and external evidence suggests that they were written around 1599-1601 (for a recent summary, see the introduction to the 2006 Arden edition). That is why scholars assume that the Hamlet play mentioned by Nashe, Henslowe and Lodge was probably a different one. But Q1 is a puzzle of its own. Is it a bowdlerized version of Shakespeare's play? Or some kind of halfway point in the transformation of the ur-Hamlet into Hamlet? We don't know.

So, what was the ur-Hamlet?

The short answer is, we don't know. Perhaps Thomas Kyd wrote an early Hamlet play and Shakespeare, acting in it, was inspired to create his own version a few years later. Or perhaps the young Shakespeare first wrote Hamlet back in the 1580s and gradually rewrote it into the version we know today. There is a vast amount of scholarly debate on these questions, but I'm not convinced that we'll ever know the truth.

And since Henslowe will never mention Hamlet again, I think we have the right to shrug and move on!

FURTHER READING

ur-Hamlet information

- G.R. Hibbard, ed., Hamlet, The Oxford Shakespeare (Clarendon Press, 1987), 12-14

- Emma Smith, "Ghost Writing: Hamlet and the Ur-Hamlet", in The Renaissance Text: Theory, Editing, Textuality, ed. Andrew Murphy (Manchester University Press, 2000), 177-90

- Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor, eds., Hamlet, The Arden Shakespeare (Methuen, 2006), 44-7.

- Roslyn L. Knutson, "Hamlet", Lost Plays Database (2012).

- Martin Wiggins, British Drama, 1533-1642: A Catalogue, vol. 2 (Oxford University Press, 2012), entry 814.

Henslowe links

- Transcript of this page of the Diary (from W.W. Greg's 1904 edition)

- Facsimile of this page of the Diary (from the Henslowe-Alleyn Digitisation Project)

Comments?

Did I make a mistake? Do you have a question? Have you anything to add? Please post a comment below!

.jpg/700px-Portrait_of_Alof_de_Wignacourt_and_his_Page-Caravaggio_(1607-1608).jpg)